- Home

-

Our Firm

- A. David Jimenez, Senior Partner - Emeritus

- Frank L. Lordeman, Senior Partner

- Randy Oostra, Senior Partner

- Thomas Strauss, Senior Partner

- Alan R. Yordy, Senior Partner - Emeritus

- John Abendshien, Partner

- William H. Considine, Partner

- Dan Hannan, Partner

- Marty Hauser, Partner

- Mark Janack, Partner

- Nancy Steiger, Partner

- C-Suite Consulting

- Our Services

- CEO Healthcare Roundtable

- Partial Client List

- Corporate Affiliate Partners & Joint Venture

- News & Updates

- Blog Posts

- Contact Us

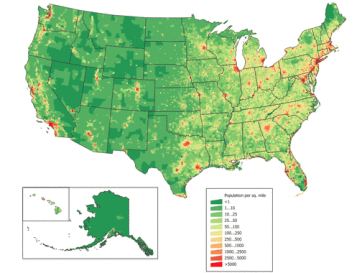

AuthorStephen C. Hanson, MPH, FACHE, Partner, CEO Adivsory Network This is the first part of a two-part introduction to a series of articles regarding health megasystems. INTRODUCTION: THE INITIAL DAYS OF THE SUPERMEDS The Clinton administration attempted to reform healthcare in the 1990s. One of the reactions to that process was the conventional wisdom that there would be ten to fifteen “supermeds” that would encompass most of the healthcare delivery in America. These systems would cover large segments of the population providing access to a full continuum of  care and access to managed care and insurance products. They would be for-profit, faith-based not-for-profit, and secular not-for-profit. With the exception of a few Catholic and other sectarian systems (and of course Kaiser Permanente that was already strong in key geographies), the supermodel did not happen. While some for-profit companies certainly had and continue to have scale, they are still predominantly focused on acute care. We can speculate as to why this did not occur. In part, because healthcare was not truly “reformed” during that timeframe. In part, because major changes in the health system tend to come very slowly. The important point is that now, nearly a generation later, these supermeds, what we are now calling “megasystems,” are very much becoming reality. They pose great opportunities for healthcare and also significant challenges which this blog will address. US population density in 2010. Source: Wikimedia commons Ten to twelve years ago, the question was often asked: how big does a health system need to be to be sustainable? The thought at that time was $5 billion plus in operating revenues in many parts of the country with significant metropolitan populations. For predominantly rural areas, there was no specific number attached, but a successful system needed to be of relative size to succeed in those geographies. Citigroup and others compared operating margins and other key metrics to discuss the importance of size and scale. Now, the “price to get in” is moving north of $10 billion annually and we are seeing the growth of systems past the $20 billion level and beyond. This blog will focus on private not-for-profit megasystems. There are unique attributes to for-profit and governmental systems on which others with more direct experience can opine. The key characteristics of successful megasystems will be: 1. They need to be successful. 2. They need to be well governed. 3. They need to be well led. 4. They need to achieve scale across broad geographies and be financially strong. 5. They need to be focused on the patients and communities they wish to serve. I. THEY NEED TO BE SUCCESSFUL Donald Berwick’s Triple Aim is a simple yet grand definition of success for the megasystem. Will the megasystem 1) Improve the health of populations? 2) Enhance the patient experience of care? 3) Reduce the per capita cost of care? Serious consideration should be given to another success metric: a “Fourth Aim” (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, Annals of Family Medicine, November-December 2014): 4) Improve the work life of clinicians and staff. (More on this specific topic in an upcoming post). The successful megasystem will need to assure that its growth is focused on achieving the “Quadruple Aim” and not just growing for growth’s sake. The mission statement, vision, values and goals for each megasystem need to be clear in terms of stating this so that all stakeholders are fully aware of the end game. Specific measurable objectives for at least three years will need to be established and reviewed/revised annually so that there is clear system-wide focus on the targeted outcomes. II. THEY NEED TO BE WELL GOVERNED A. System The top-level governance of the megasystem will need to increasingly resemble that of other large corporations albeit with a clinical leaning. Lay executives from public and major private companies with experience in sizable, complicated organizations will be required to a much greater extent than currently. Specific skill sets within megasystem governance are not unlike smaller organizations but on a MUCH larger scale and include: -Strategy -Population health/value based services -Legal, compliance -Information systems and security -People/human resources/culture -Performance improvement (LEAN/Six sigma) In addition to governing body members from nonclinical industries, consideration should be given to leaders from large clinical companies (big pharma, medical devices and equipment) and even from non competing health systems. On the clinical side, there is a greater need for physicians and nurses including in many cases academicians. Source: Creative Commons Of course for faith-based organizations, there will be representation of the appropriate religious order(s).

The current thinking of best practices of having fewer than fifteen board members (some say less) should continue. Key committees should be relatively few in number and cover the following areas to meet the Quadruple Aim: -Strategy -Quality/clinical/population health -Audit/compliance/risk -Finance/information systems -Executive compensation -People. There is no magic frequency of meetings for the system board and that of committees. After years of experience, my opinion is that quarterly meetings are too infrequent and monthly meetings are too frequent. Something in the range of six to seven meetings per year (including board retreats) should work provided that there is good communication between meetings. There will likely be a need for reasonable compensation for system directors given the demands of the position. B. Region/local The fiduciary and ultimate clinical responsibility and accountability is with the system board. That said, there will need to be some kind of governance at the region/local level. This needs to move away from the financial emphasis that some local boards focus on to the actual accomplishment of the Quadruple Aim. Local governance should involve significant physician and nurse input. It should incorporate any local accountable care organization, clinically integrated network and other related activity. Philanthropy is another significant opportunity for local governance. III. THEY NEED TO BE WELL LED The C-suite of the megasystem will need to include people who can work in large complicated organizations and still feel connected to patients and accountable care and other population health vehicle “members.” While the heavy lifting of these relationships by necessity will rest with the regional and local leadership, it is imperative that the system leaders realize that health is a people business and one that is still predominantly local. New and creative ways to being virtually present will be critical so the leadership does not lose focus on why the health system exists. We will not cover every position in the future megasystem C-suite but here are some to be covered in general with more to follow: 1)Chief Executive Officer Obviously experience in large complicated organizations. My bias that healthcare be the background but might there be opportunities (in addition to seasoned healthcare lay executives and physician leaders) for CEOs to come from big payors, big pharma, medical device companies, etc.? Excellence in governance and all types of external relationships. Communication skills to potentially tens of thousands of internal and external stakeholders. As they say, a “high tolerance for ambiguity.” Driving all this is a laser focus on the mission, vision and values of the megasystem. 2) Chief Operating Officer While there has been a mini trend toward elimination of this role in some health systems, it seems that the need for the chief operating officer to drive excellence in the megasystem is more critical than ever. There will be opportunities for physicians, nurses and other clinicians in this role. In addition there is some presence of a dyad model where the COO and a chief medical or clinical officer serve together in the office of the CEO. More on this below. 3) (Administrative) Chief of Staff There is more current discussion including some excellent thought from the Healthcare Advisory Board about this. In my prior experience as COO in hospitals and then health systems, my function generally played this role. However now that organizations are so complex and the need for even the most talented CEOs to be “joined at the hip” with the skills that this role can bring in organizing and integrating talented teams, this function is critical. 4) “Chief Clinical Officer(s)” The clinical leadership needs in many megasystems will be so great that there may not be one overall chief medical officer but instead multiple MD/DO executive positions. These will include overall safety/quality/experience, general medical relations, leadership within health plan, population health and value based services, service line development and clinical input in such areas as supply chain management and leadership of “employed” physicians. Most megasystems will have academic affiliations and the related education and research components so appropriate clinical (and lay) leadership will be necessary here as well. A personal bias, but there must be a Chief Nursing Officer in the C-suite. This individual will be coordinating nursing and other clinical care across the continuum of care in multiple geographies. Please note that the MDs and nurses in these roles will play a pivotal role in the Fourth Aim above. 5) Chief Financial Officer This role arguably more than any other long-existing role in the C-suite is bound to change the most in the next decade and the title itself may change to reflect the broader and more forward looking nature of the role. More to come in a future blog but as someone who has been very close to hospital and health system financials for many years, this will be a position as closely aligned to the CEO as the COO and Chief of Staff and nearly as aligned to the System Board as the CEO. Some companies (Warbird) are starting to write about this changing role and I agree with the concept of a strategic CFO. There will be much greater involvement in overall strategy, nontraditional sources of capital and financing in general, understanding of financial risk. And while the overall chassis of the megasystems we describe will be not-for-profit, there will be many for-profit subsidiaries and transactions involved. The sheer size and scope of megasystems will require that they look increasingly like complicated public organizations from a financial point of view. Some specific areas of emphasis: A. Ventures. Several existing or emerging megasystems (Ascension, New York Presbyterian, Providence) have formed their own ventures vehicles while others have joined forces with other systems (not-for-profit and for-profit) to invest in and partner with early stage to mid stream companies. This is partially for returns but more exciting to me the chance to continue to transform health and healthcare in partnership with these new companies. The successful megasystem of the future will need to create its own ventures entity or join forces with others. This approach has to be linked directly to the health system’s overall investment strategy as well. In any scenario we argue that this responsibility is within the CFO’s purview. B. Revenue cycle/”managed care.” Much has been written lately (Healthcare Advisory Board, others) about the need to more fully automate and modernize revenue cycle to assure that it is achieving its maximum efficiency in collections at a lower amount of collection expense. Although there has been incredible focus in revenue cycle for years, we have only scratched the surface. Further, traditional managed care contracting will continue to morph into creative “win/win” values based approaches. These will be within the health system and with its physicians and any wholly owned health plans and also in partnership with other health plans, external accountable care partners and so on. The strategic CFO will provide key leadership in this area. C. Supply chain. Like revenue cycle, this is an area that will see tremendous advancement and will require moving from a customer/vendor “purchasing” approach to one which creates a true partnership between the heath system and the companies with which it does business. Pharmaceutical utilization and purchasing will be integrated. This new supply chain process will include joint risk contracts and other creative partnership relationships. This will require clear coordination between and among the chief physicians, nurses, pharmacists and other clinicians, but again under the purview of an enlightened CFO. D. Expanded ratio analysis, analytics, information systems, LEAN/Six Sigma, risk management. These are all critical areas in which the future CFO needs to be intimately involved. In some cases these will be shared with other C-suite members but the CFO will need to be the integrator of these functions. More to come on this critical C-suite role. 6) Strategy, Marketing, Business Development The role or roles within these areas will also see dramatic change as healthcare (finally) becomes consumer centric and, I believe, more employer sensitive. Strategy will need to continue to look at five and even ten-year plans while assuring that the megasystem is able to move quickly quarter to quarter in meeting the needs of its markets. The overall patient experience throughout the “continuum of care” will need to expand to include members/clients of insurance products and other value based services. Techniques will be “borrowed” from other industries and adopted as appropriate within healthcare; this will result in part from attracting people in these areas from outside of healthcare working for very innovative companies. Data and analytics will be even more important in decision-making and implementation and as discussed above will need to coordinated by the CFO. 7) People, Culture, Innovation These areas will continue to evolve into the driving of a true system-wide culture with less emphasis on the traditional labor relations areas. Again, more to follow but these individuals may increasingly come from large companies outside healthcare. The above mentioned laser focus on mission, vision, and values will need to create the culture across the megasystem. We list innovation here, as that has to be part of the successful megasystem’s culture. There seems to be a trend toward hiring chief innovation officers. This author is not convinced that is necessary as innovation needs to be part of each C-suite member’s role starting with the CEO. If it is deemed to be critical, it could be placed in People and Culture or Strategy/Marketing or directly in the office of the CEO. There will be other key areas within the C-suite that will develop and can be discussed at the right time. Coming Next in the Second Part of this Introduction to Megasystems: Scale, Financial Stability, and Patient/Community Focus This series represents the opinions of Stephen C. Hanson, MPH, based on serving in CEO and COO/significant operational and strategic roles in five different health systems and four standalone hospitals in seven states as diverse as Texas, New York and Kentucky. References that informed this piece are mentioned. Steve can be reached at [email protected].

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Copyright © 2017 - 2024 All Rights Reserved.

- Home

-

Our Firm

- A. David Jimenez, Senior Partner - Emeritus

- Frank L. Lordeman, Senior Partner

- Randy Oostra, Senior Partner

- Thomas Strauss, Senior Partner

- Alan R. Yordy, Senior Partner - Emeritus

- John Abendshien, Partner

- William H. Considine, Partner

- Dan Hannan, Partner

- Marty Hauser, Partner

- Mark Janack, Partner

- Nancy Steiger, Partner

- C-Suite Consulting

- Our Services

- CEO Healthcare Roundtable

- Partial Client List

- Corporate Affiliate Partners & Joint Venture

- News & Updates

- Blog Posts

- Contact Us

RSS Feed

RSS Feed